Courtesy of Geraldo Rivera

Willowbrook State School opened in 1948 as the largest institution in the world for the treatment of people with developmental disabilities, separating them from the mainstream of society. In 1938, the New York State Legislature had authorized the building of a school for what they then termed “mental defectives.” The Willowbrook site was selected and the buildings were erected in the early 1940s.

Courtesy of David Goode Collection

However, when the U.S. entered the Second World War, the site was turned over to the military for use as a hospital and prisoner-of-war camp – Halloran Hospital – that operated until 1951. As the hospital was closing down, the entire site returned to its original intended purpose as the Willowbrook State School.

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, College of Staten Island/CUNY

Places like Willowbrook had existed for hundreds of years in Europe. U.S. physicians imported European models into the U.S. in the 1800s. New York State built its first large institution in 1852, and subsequently many others. When Willowbrook was built in the late 1930s, it was by no means unique. Many similar but much smaller institutions existed in New York State and across the country at that time.

Courtesy of Diane Buglioli Collection

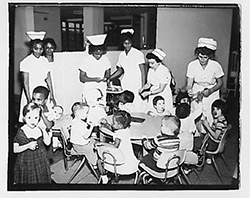

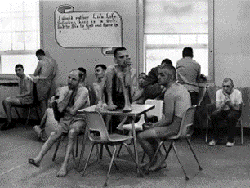

From its opening, the Willowbrook State School was presented to the public as an ideal place for residents. Over time, a number of photographs depicting numerous staff helping well-served residents appeared in newspapers and other publications. Residents were depicted receiving therapies and engaged in activities that included job training. In reality, in many buildings, residents had few staff assigned to their care.

Courtesy of Jon Senzer, photographer.

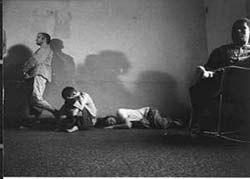

In order to manage many residents with few resources, practices developed that could cause harm. One of these practices was the use of “Cripple Carts” -- rolling wooden carts originally used for residents who had physical disabilities, like Spina Bifida, who could not use wheelchairs. At Willowbrook, these carts were adapted more generally to make it easier for a single staff member to move many residents around at once. As a result, residents were crowded into carts and parked in dayrooms for hours with little stimulation or care. This neglect robbed residents of the opportunity to reach the developmental potential they would have had if they had been treated differently.

Courtesy of Vickie Schneps

Many families agonized over the decision to place their children in such impersonal facilities where staff struggled to meet even the children’s basic needs. Rather than keeping their child at home where almost no community therapies or education were available, many families hoped that institutionalization would be in the best interest of their child.

Courtesy of Bob Adelman, photographer/Adelman Images LP

In fact, as budget cuts consistently deepened and the number of residents grew, Willowbrook became an inhumane warehouse. When Senator Robert F. Kennedy visited the institution in 1965, he argued that the housing of 6,000 there had made Willowbrook “a snakepit.”

Courtesy the New York State Office for People With Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD)

Families whose children resided in the School, as well as staff who worked there, had long advocated for change. Only in the early 1970s were they successful in making those outside of the system aware of the problems inside the facility.

Courtesy The Staten Island Advance and William Bronston.

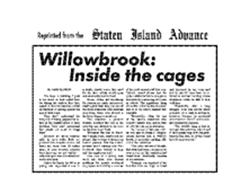

For a month in the fall of 1971, Staten Island Advance reporter Jane Kurtin published a series of daily articles revealing the appalling conditions at the School. Kurtin’s ground-breaking journalism coincided with and amplified parent protests about conditions. She was accompanied by photographer Eric Aerts, who captured chilling images of the conditions in which residents were living.

Courtesy Geraldo Rivera

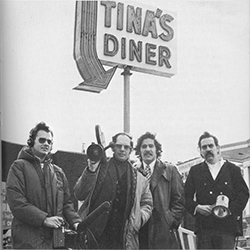

Willowbrook physicians William Bronston and Michael Wilkins made families and the community aware of the problems caused by understaffing and overcrowding. In 1972, Drs. Bronston and Wilkins brought ABC reporter Geraldo Rivera onto the grounds to film. Rivera’s televised exposé brought Willowbrook State School to national attention in an explosive and realistic investigation into the cold, stark, inhuman institutional setting.

Most importantly, in combination with Kurtin’s reporting, the exposé gave a platform for residents and their families to be heard and set the foundation for a 1972 class-action lawsuit that established that Willowbrook residents had a constitutional right to be protected from harm.

Courtesy Geraldo Rivera

The harm from which residents had a right to be protected – abuse and neglect – was not simply the result of “bad” people working there. In fact, the vast majority of caregivers did their best to help residents under horrible conditions. But, typically, one nurse was responsible for up to 100 residents’ care, sometimes in multiple buildings. To understand why things became as bad as they did, one needs to appreciate several factors.

Courtesy The Staten Island Advance

It is important to appreciate that Willowbrook was a “total institution” – that is, a place where a large number of powerless people are put under the total control of a small number of powerful ones. Scholars have long known that this creates forms of social pathology, including physical and mental abuse. Both residents and staff are powerfully influenced by such places. They both tend to conform to their assigned roles.

Courtesy Bill Bronston

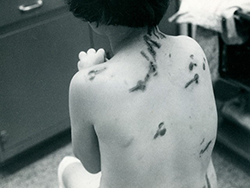

This creates an atmosphere where caregivers are able to justify to themselves doing things they would never do outside the institution. Many instances of staff abuse of residents happened at Willowbrook. This photograph shows wounds a young female resident suffered when a staff member beat her repeatedly with large, heavy keys. Worse incidents were also documented. The dynamic of abuse of residents was not unique to Willowbrook. It existed all over the country at many similar total institutions.

In addition, Willowbrook operated at a time when persons with disabilities were devalued by society. The growing disability rights movement had yet to gain recognition and, as with other underrepresented communities, the full humanity of persons with disabilities was not generally appreciated. Families with children with disabilities often endured shame and social ostracism.

When workers came to Willowbrook, they usually had no experience with or knowledge of disability. When they arrived, they would find the residents in crowded conditions with inadequate clothing, food, or education. This contributed to their perception of residents as less than human.

Courtesy the Staten Island Advance

Inadequate numbers of staff, largely untrained, struggled with their responsibility for too many residents and without resources. Then the budget cuts that occurred, especially in the 1960s, made these shortages even more critical.

Courtesy Bill Bronston Collection, The Archives & Special Collections, College of Staten Island/CUNY

A final reason why Willowbrook became as bad as it did was the indifference of New York State government. Employees -- including doctors -- who raised concerns about conditions were fired, while advocates were ignored or treated with arrogance by State officials. The State was well-aware of conditions but even under criticism refused to do anything about them until forced to by public outcry, media scrutiny, and lawsuits in the early 1970s.

These efforts formed the foundation of a disability rights movement that is still underway. Families and advocates demanded an appreciation of the humanity of all people with disabilities. Self-advocating former residents, such as Bernard Carabello, told their stories and resisted attempts to silence them and to erase the history of Willowbrook. Together, this coalition of advocates worked to create community care systems and to close large institutions through legal actions.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, The College of Staten Island/CUNY

In 1975, a Consent Judgement was entered in the 1972 Willowbrook lawsuit. That Judgement ordered that Willowbrook residents receive humane treatment and adequate clinical and educational services. This also set in motion the eventual closure of Willowbrook in 1987 and began the development of community-based services. It mandated a reduction from 6,000 to 250 residents by 1981.

Text on the Image:

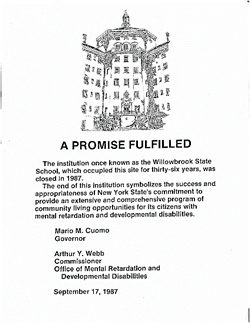

The institution once known as the Willowbrook State School, which occupied this site for thirty-six years, was closed in 1987.

The end of this institution symbolizes the success and appropriateness of New York State’s commitment to provide and extensive and comprehensive program of community living opportunities for its citizens with mental retardation and developmental disabilities.

Mario Cuomo, Governor

Arthur Y. Webb, Commissioner, Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities

September 17, 1987

Courtesy Hal and Laura Kennedy

These changes were revolutionary. They can be linked to the placement of people with developmental disabilities in community residences, the growth of voluntary agencies, the expansion of special education and day programs, and the training of direct-care workers, therapists, teachers, and administrators.

Cover page for the class-action lawsuit that led to the Consent Judgement in 1975, listing the plaintiffs, made up of advocacy organizations and individual residents with their guardians.

Plaintiffs:

New York Association for Retarded Children, Inc.;

Benevolent Society for Retarded Children, Willowbrook Chapter, of the New York State Association for Retarded Children;

Lara R. Schneps, by her father Murray B. Schneps;

Nina Galin, by her mother Diana Lane McCourt;

Anthony Rios, by his father, Jesus Rios;

David Amoroso, by his mother Rosalie Amoroso;

Rose Evelyn Cruz, by her father Francisco M. Cruz;

Barry Friedman, by his father Melvin Friedman;

Lowell Scott Isaacs, by his father Jerome M. Isaacs;

Antoinette Magri, by her mother Sandra Magri.

Defendants:

Nelson Rockefeller;

Alan D. Miller, M.D.;

Roderic Grunberg, M.D.;

Robert E. Patton;

Charles Schleifer;

Jack Hammond, M.D.;

Robert W. Hayes;

Bertram Pepper, M.D.;

A. Anthony Arce, M.D.;

James M. Murphy, M.D.;

Manny Sternlicht;

Milton Jacobs, M.D.

Courtesy The George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

Along with the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act, the Willowbrook Consent Judgement helped lead to later key legal protections, including the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the U.S. Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision (1999).

Courtesy the Staten Island Advance

The broader impact on care for persons with disabilities included the creation of a range of community services, many made possible through the work of State Assembly representative Elizabeth Connelly. These services were also made available to those who had never been institutionalized. This gave new options to families that were more supportive of quality of life for all involved than institutionalization could ever be.

The Willowbrook story provides a stark reminder of the societal loss when people are segregated due to their difference, whatever that difference may be. At the same time, it reveals how advocacy and visibility can change this.

Courtesy Russ Cohen

The Willowbrook story also reveals how the devaluation of persons with disabilities could lead to their use in unethical research. From its opening, medical and psychological research was central to Willowbrook’s mission and produced many contributions to medicine and habilitation.

There were programs of research on electroshock therapy, drug therapies, endocrinological studies, genetic diseases, and communicative diseases such as rubella and hepatitis (common at Willowbrook). Psychologists conducted research on resident intelligence, therapies involving parents, the effects of institutionalization, and testing and assessment with special populations.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, The College of Staten Island/CUNY

Today, some research conducted at Willowbrook is held up as an example of unacceptable breaches in human subject research. The most infamous of these are the Willowbrook Hepatitis Studies of the 1950s and 1960s. In these, children at Willowbrook were infected with hepatitis to study the disease’s progression. The lead researcher used highly unethical procedures to convince parents to allow their children to be so infected. The resulting scandal and legal challenge successfully blocked medical research at Willowbrook through a 1973 US District Court ruling. This ruling is often mentioned as one of the main reasons there are now federal ethical guidelines for medical research.

Courtesy Archives and Special Collections, The College of Staten Island/CUNY

On May 2, 2000, the College of Staten Island/CUNY and the Staten Island Developmental Disabilities Council sponsored an all-day conference at the College attended by over four hundred people recognizing the 25th anniversary of the Willowbrook Consent Judgement. This conference highlighted the significant events and individuals that led to the eventual closing of the gates at Willowbrook and the opening of the doors of opportunity for thousands of New Yorkers with intellectual disabilities.

Courtesy Staten Island Developmental Disabilities Council

Spurred by a conviction that nothing like the Willowbrook story should ever happen again, the Council – the primary advocacy group on Staten Island for people with disabilities and their families – formed the Willowbrook Property Planning Committee in 2005. The Committee began to work on collecting and preserving the history of the Willowbrook State School to increase the visibility of the stories of those who had once lived and worked in the facility.

©College of Staten Island/CUNY

In 2012, the Council partnered with other stakeholders – the College of Staten Island/CUNY, the NYS Institute for Basic Research (IBR), and the Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) – to establish a memorial walking trail on the former Willowbrook State School site that is now the Willowbrook Mile.

©College of Staten Island/CUNY

The Willowbrook Mile Committee dedicated itself to ensure that whatever the final format this memorial should take, that presence had to be inclusive, progressive, productive, creative, collaborative, sustainably-designed, and both philosophically and physically universally-accessible to people of diverse abilities and needs. This unique project aims to preserve the site’s history and create a visionary presence that commemorates the continuing struggle for social justice for all people of all abilities.